Alas, Mr. Trump

Alas, Mr. Trump

You are Not the Only Problem

I know you won’t like it

But it’s the naked truth

They smiled and cheered

And raised their weapons

Of warfare screaming

Bravo as you preened

Forgive me for being

So blunt or don’t forgive me

Because it really doesn’t matter

You are Not the Only Problem

In the chaos of last week’s attack on Congress, it was crystal clear. Several weaponed-up angry white men shouted, ‘This isn’t Trump’s war. It’s ours!’ They’d moved way beyond Trump who, it seems, was the high-ranking inciter and/or supporter of violence they’d dreamed of for years. A cover and a disposable figure. An excuse for mayhem and murder.

Before and after becoming POTUS, Mr. Trump was and still is an inciter of white, mostly male pride, privilege, and crude violence unleashed, unafraid, and unrepentant. Is impeachment enough to satisfy the last four years of incitement to violence and disdain?

I don’t have answers. Nor will we find answers until we white citizens take seriously the history of the USA. For decades we’ve endured or ignored regular disruptions of mostly white “I’ll do it my way” men and women. Including standoffs by white men armed with rifles in this ‘land of the free and home of the brave.’

For the most part, they got away with it then and they get away with it now. Yes, a token number of people are being arrested for last week’s attack on Congress. Still, many have disappeared into the woodwork. There’s no way this attack would have happened if the perpetrators had been black.

Here’s now W. E. B. Du Bois puts it in his early 1900’s essay, “The Souls of White Folk” (emphasis mine).

Murder may swagger, theft may rule and prostitution may flourish and the nation gives but spasmodic, intermittent and lukewarm attention. But let the murderer be black or the thief be brown or the violator of womanhood have a drop of Negro blood, and the righteousness of the indignation sweeps the world. Nor would this fact make the indignation less justifiable did not we all know that it was blackness that was condemned and not crime.

Do we have the guts to condemn white crime? And to hold white Mr. Trump accountable for collusion, if not incitement?

Praying for courage to change the things we can,

Elouise♥

© Elouise Renich Fraser, 13 January 2021

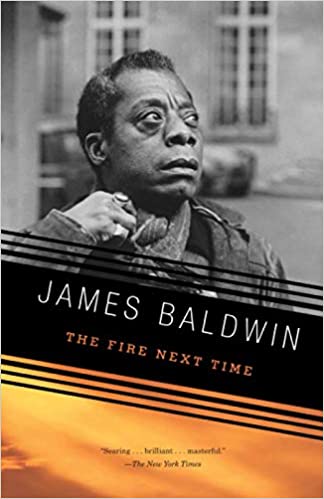

Image found at nytimes.com